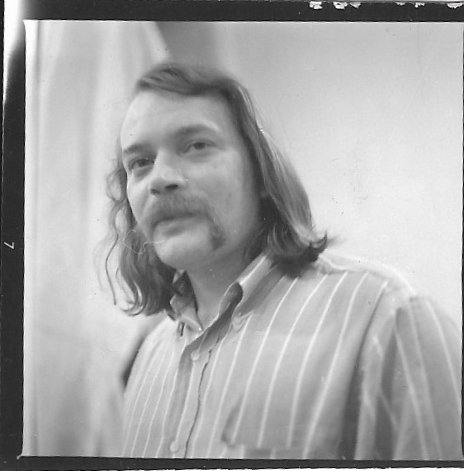

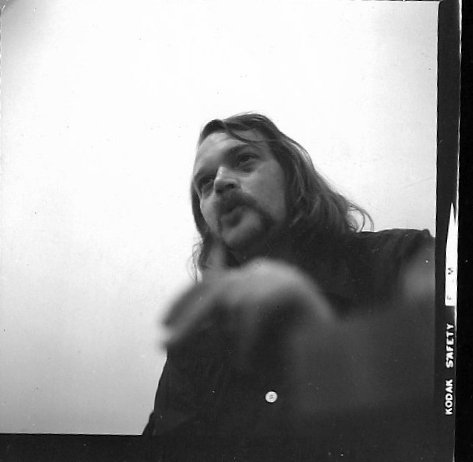

Kenneth Showell

About Ken:

Kenneth Showell died in the Spring of 1997 at the age of 58. He left behind 30 years’ worth of work — nearly 200 canvases, plus hundreds of watercolors, pastels, and sketches — all carefully stored and documented. Showell is best known for the paintings he produced in the mid ’60s to early ’70s. His work, alongside other significant artists of that time, played a crucial role in the critical debates concerning abstract painting in the late 1960s.

The son of a sheet metal worker, Kenneth Leroy Showell was born in 1939 in Huron, South Dakota and grew up in Omaha, Nebraska. After receiving his B.F.A. at the Kansas City Art Institute and an M.F.A. from Indiana University he moved to New York City in 1965, setting up a studio in SoHo. Ken’s work garnered significant attention and was included in numerous museum exhibitions and private collections.

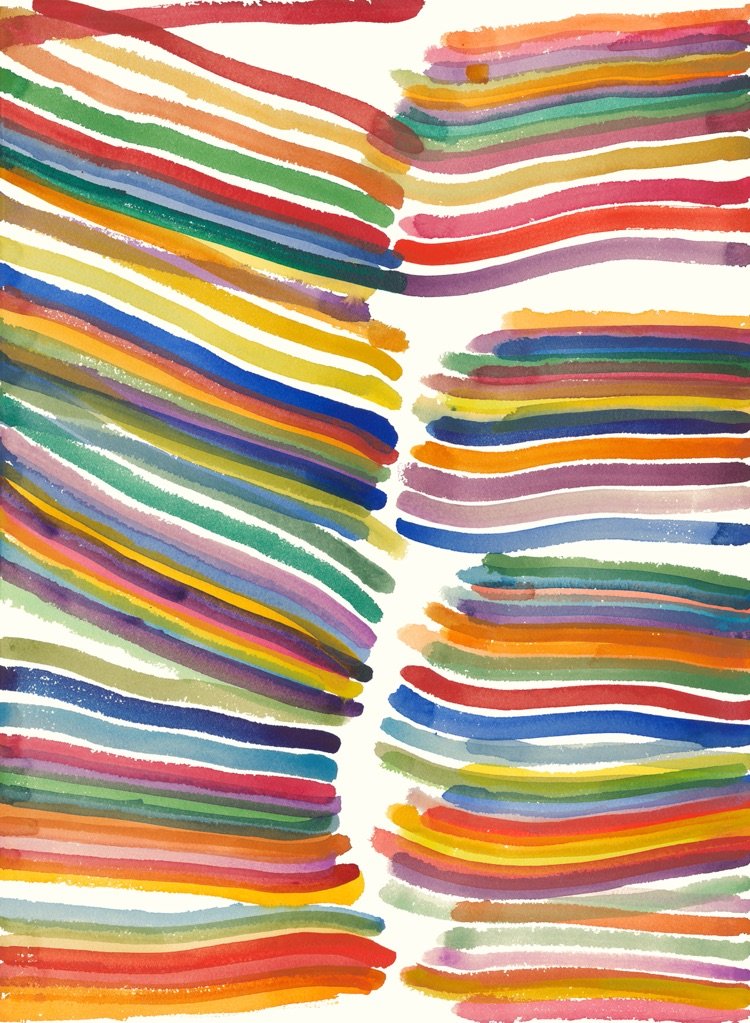

Showell had a reputation for making paintings that had a sense of spontaneity, sensuousness and opticality. His 30-year history as a painter is marked by his remarkable ability to handle color, regardless of the subject or process. His abstract work occurred in a very vibrant and vital period in American abstract development and continues to gain attention, appearing in group exhibitions and museum collections. No matter what form the visual took, for Showell there was always a consistency of conceptual thought and color resonance that makes his work unique.

For this feature, Grand Image conducted an interview with Hannah Palin, Ken’s daughter. Hannah was a museum curator for the University of Washington for over two decades. She now manages Ken’s vast collection of artwork.

Grand Image: Please tell us a little about the depth of Kenneth’s collection. How many pieces do you estimate he created? How do you see his style change and refine over the years?

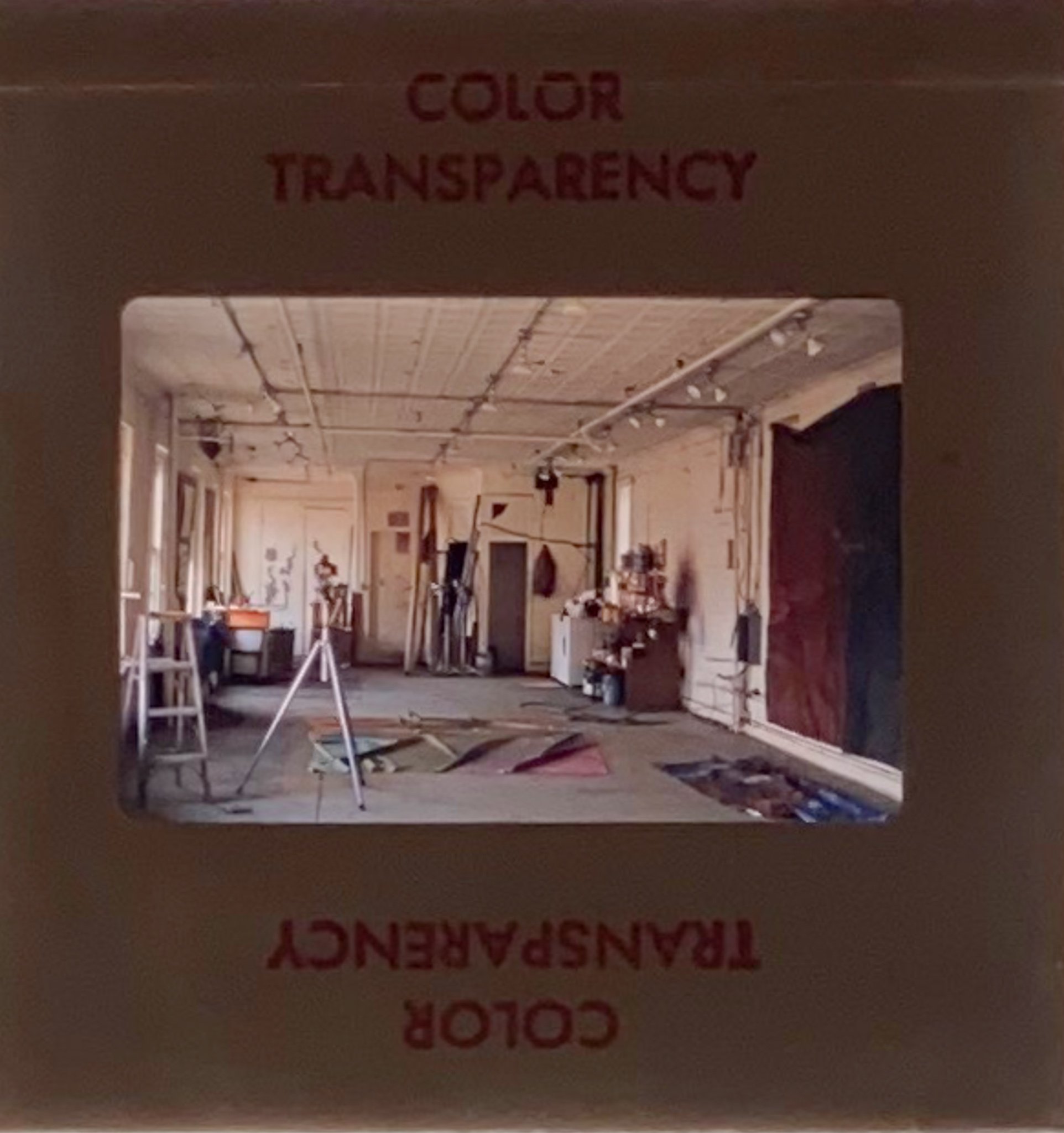

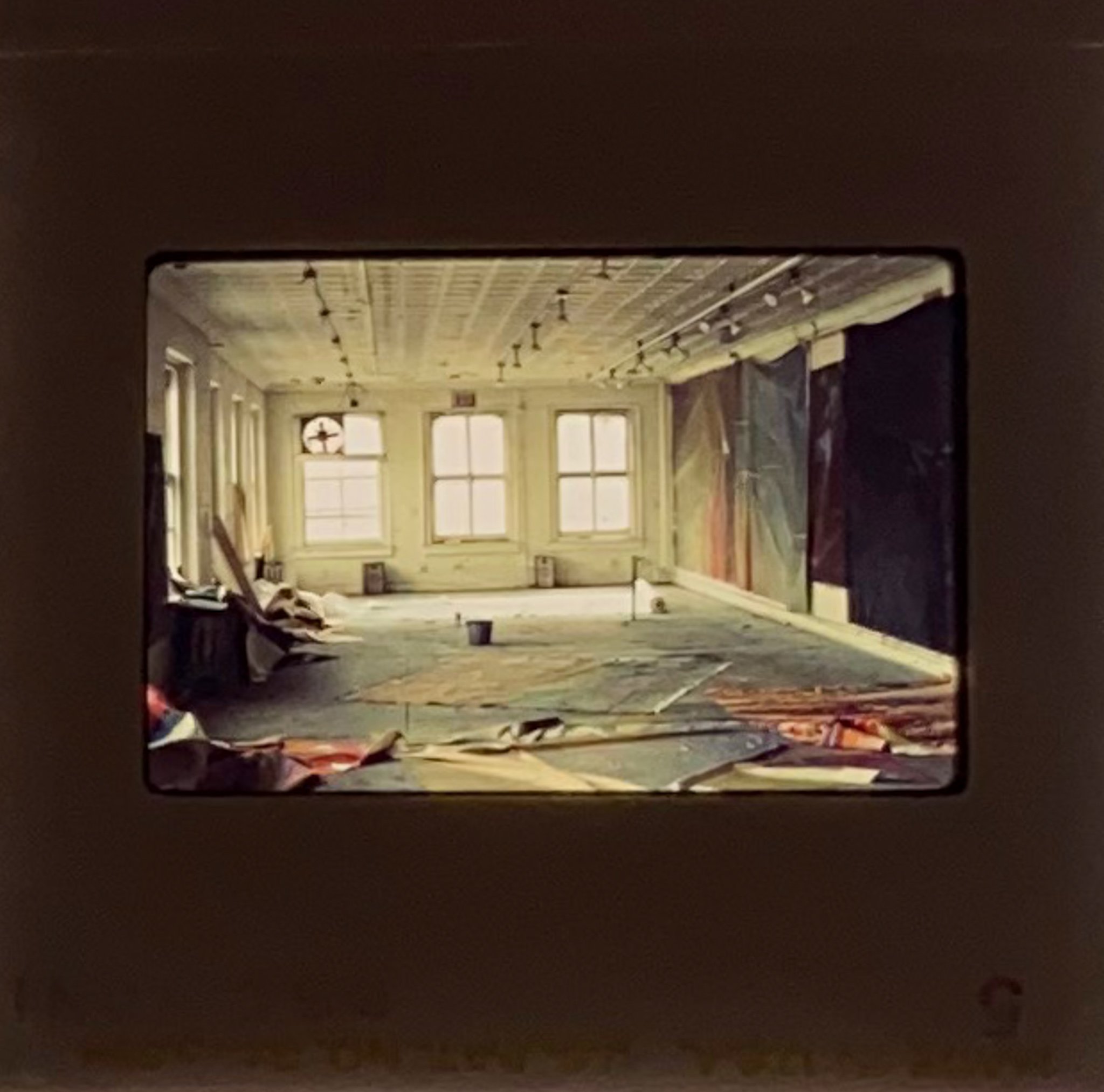

HP: In 2018, I received a storage pod filled with work created by my estranged father, Kenneth Showell, a New York painter and photographer. Immediately after his death in 1997, the family moved the collection from Ken’s studio in New York City to my uncle, Terry Showell’s, home in Omaha, Nebraska. The family carefully stored and cared for the work, bringing it out for a few shows curated by my uncle Don Showell, including a retrospective in 2006 at the Hot Shops Art Center. When Terry passed away in 2018, the family decided it was my turn to take on the role of caretaker, so the collection moved once more, this time to Seattle.

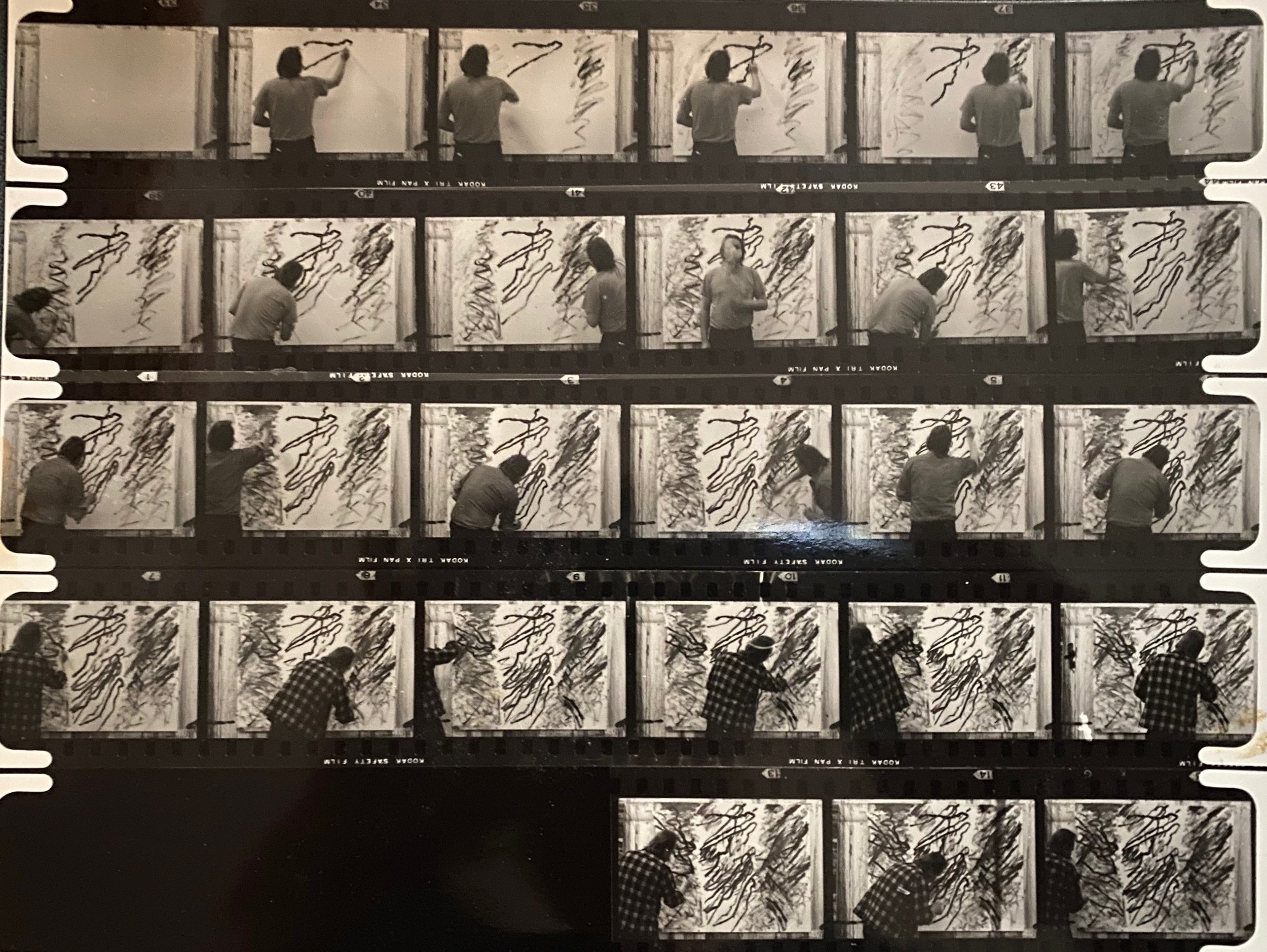

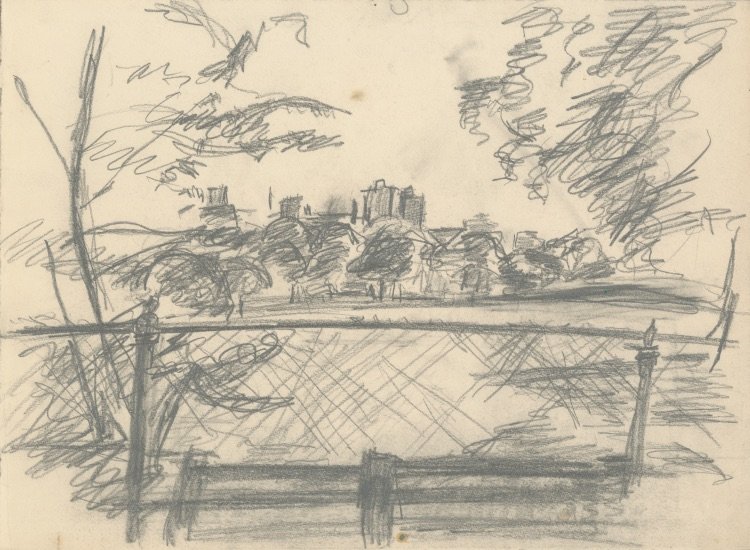

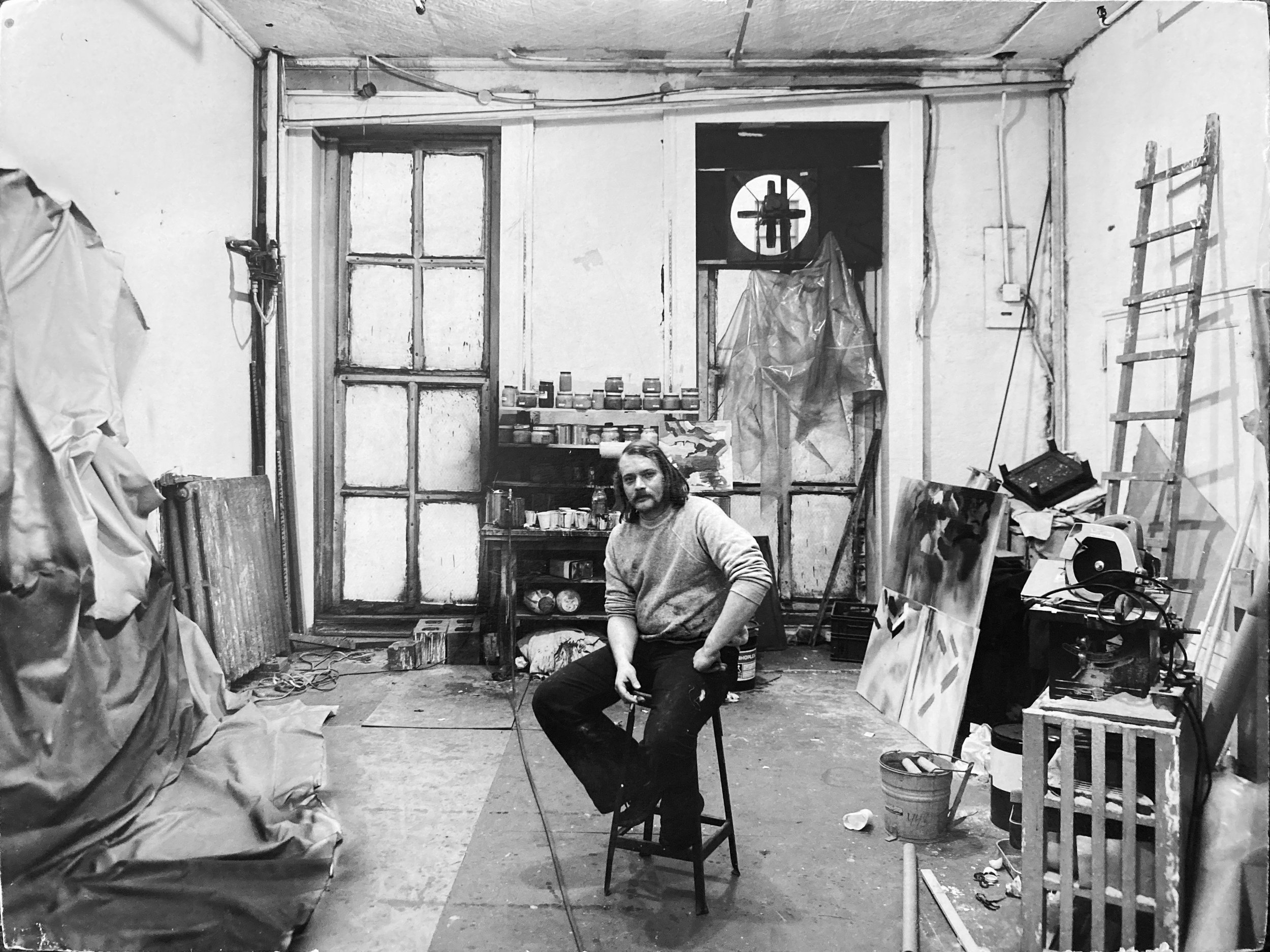

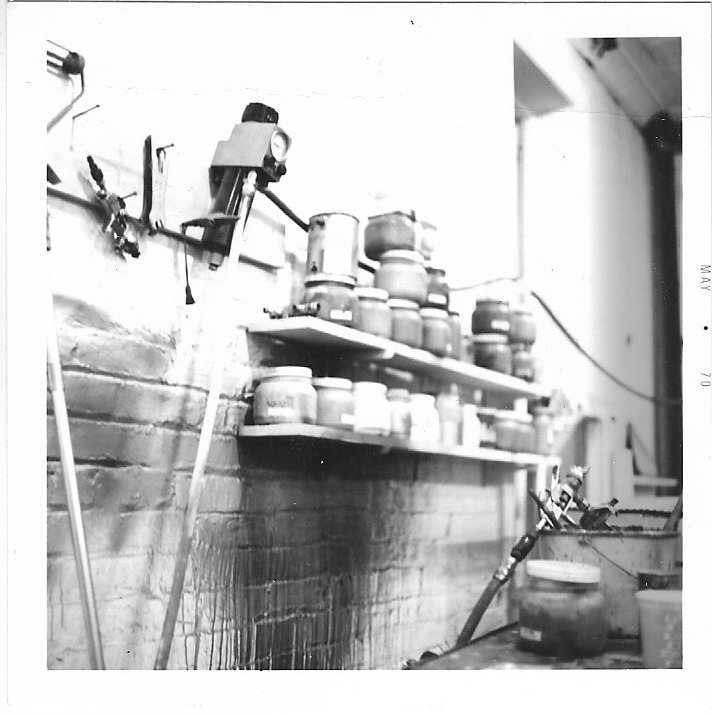

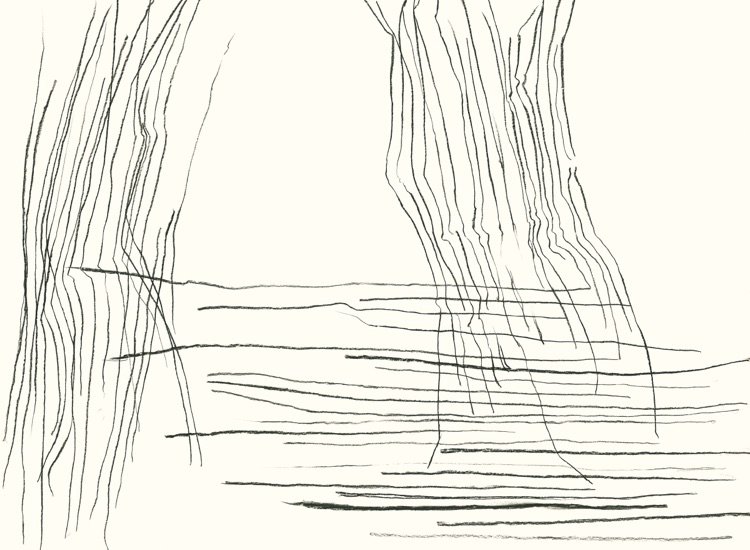

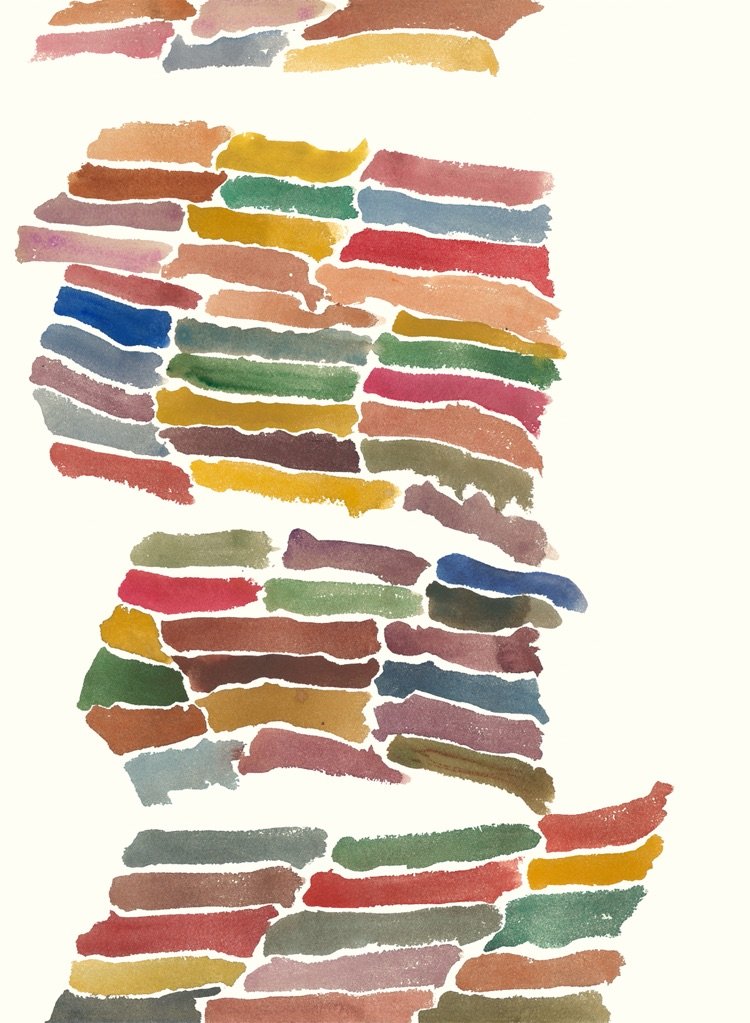

I’ve spent five years documenting, researching, and organizing my inheritance of over 1300 canvases, drawings, pastels, watercolors, sketches, and studies for larger work. In the beginning of Ken’s career, he was focused exclusively on the abstract. He was best known for his spray paintings which had the trompe l’oeil effect of appearing wrinkled when the canvas was flat. Ken credited his brother Don, an auto-body worker at the time, with teaching him how to operate a spray gun. He used this simple tool to create large scale works by balling up sections of canvas, spraying them with paint, drying and stretching them, then repeating the process. This style came to be included in a movement labeled Lyrical Abstraction, a term coined by the collector Larry Aldrich to describe those painters who were moving away from the "geometric, hard-edge, and minimal, toward more lyrical, sensuous, romantic abstractions in colors which are softer and more vibrant.”

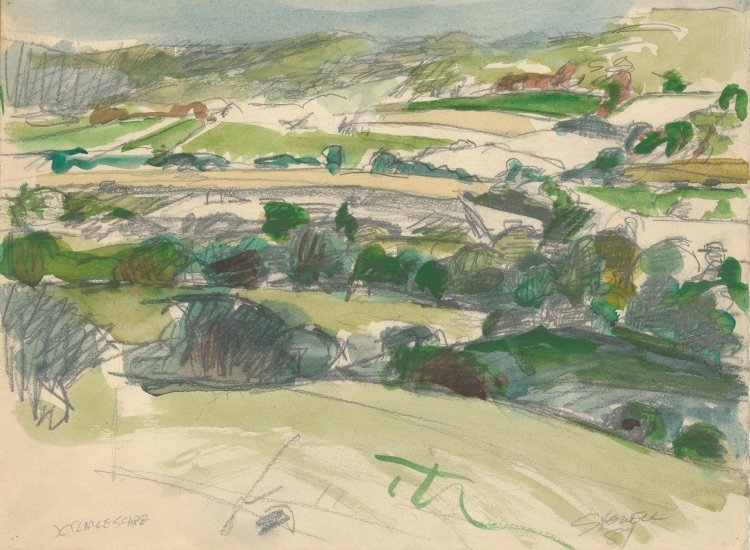

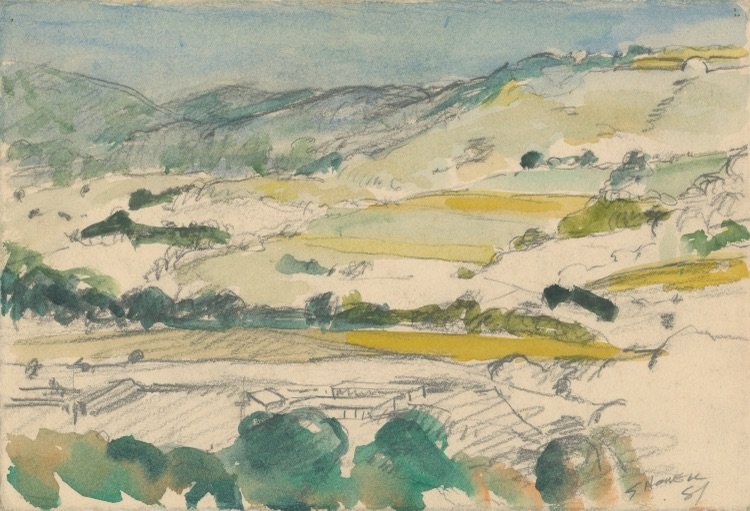

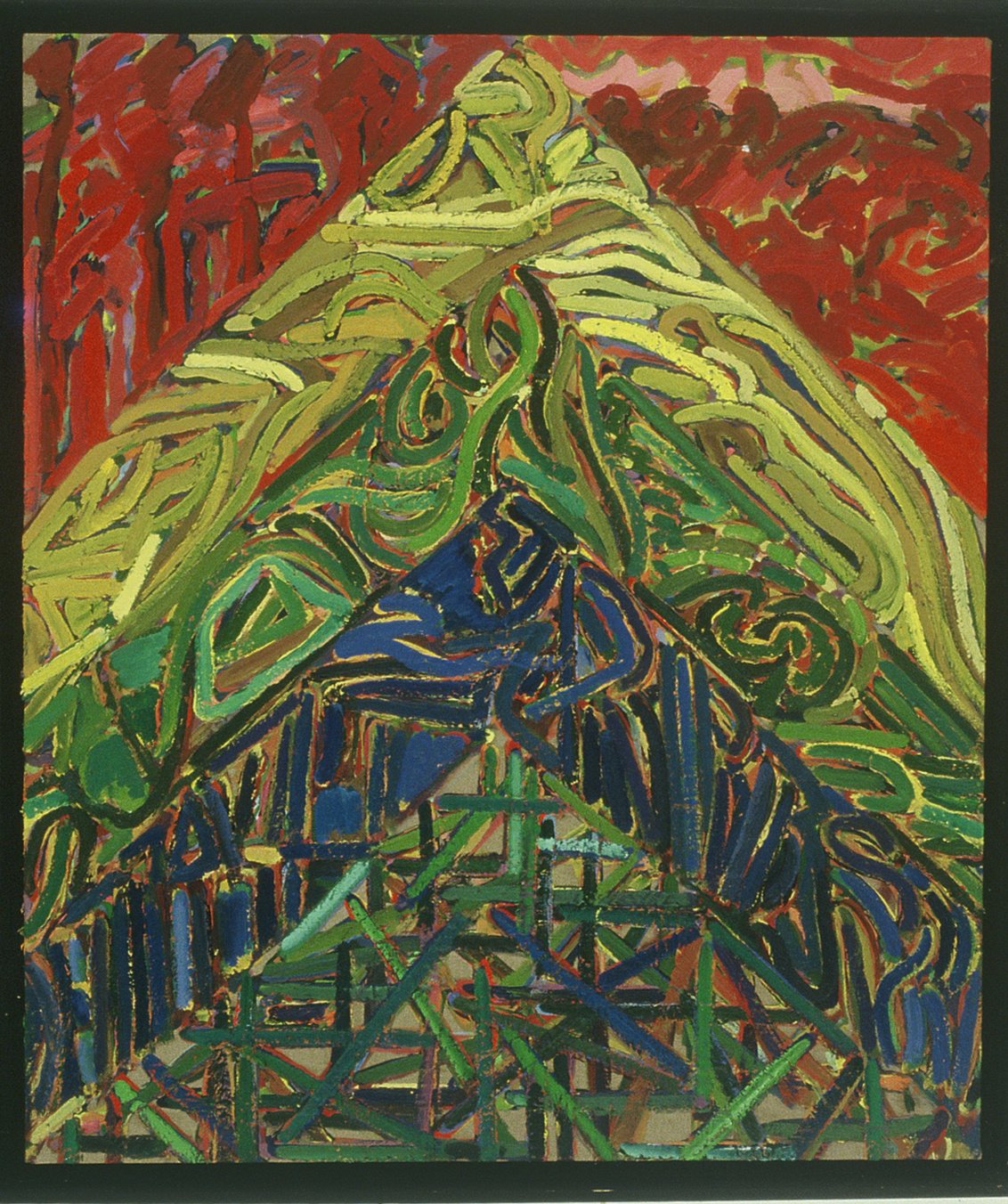

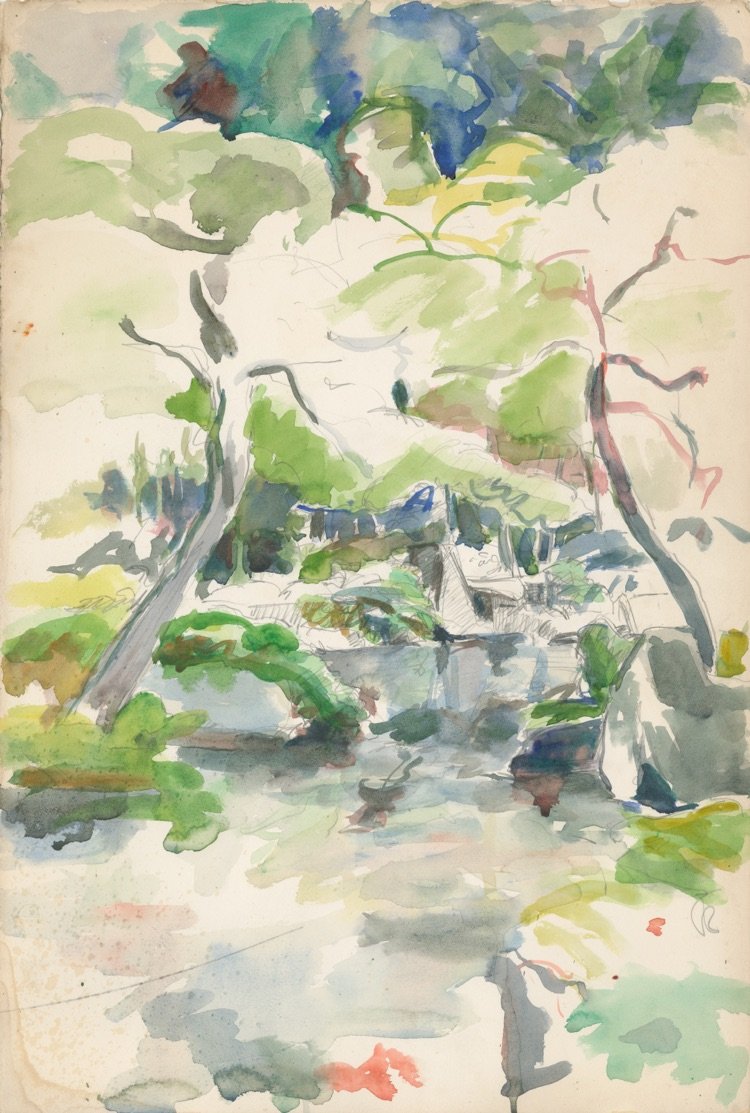

His work began to evolve in the mid-1970s because, as he said in a Smithsonian Archives of American Art interview, “It quit being a surprise, completely.” Always curious, always experimenting, he slowly incorporated landscapes into his abstracts. By the mid-1980s through the end of his life, he was more and more enamored with the idea of how you represent the real. He produced landscapes and still lifes, exploring a form of plein air painting that used video to capture a scene that he would later bring into his studio to paint at his leisure. His landscapes employed the same vibrant color and distorted perspective as his abstracts, making them just as interesting and vibrant as his early work.

Grand Image: How did your father’s friendships and relationships affect his work?

HP: Ken moved to New York City in the mid-1960s, feeling the pull of the vibrant art scene there, after graduating from the Kansas City Art Institute and Indiana University. He found himself in a group of painters like Dan Christensen and Ronnie Landfield, those featured in New York 10/69 and many, many others. It was a network of fellow artists all working and trying to make a name for themselves. Both Dan and Ken worked with spray paint early on in their careers, and Landfield’s use of color must have also been an influence. Ken spent time at Max’s Kansas City, a bar where artists, musicians, and tastemakers found a home, and worked at Remington’s, and Fanelli’s, among other downtown bars frequented by artists. Those connections with fellow painters, where they drank and talked about art, had to affect his work and spark innovation.

Later in his career, Ken photographed other people’s artwork for exhibits, catalogs, and documentation. He was known, unofficially, as the Town Crier, traveling from studio to studio, talking about art and technique with his clients. It seems everyone knew him and held him in high regard. Most of them weren’t even aware that he himself was a talented artist with skills rivaling their own.

Grand Image: As his daughter, are you proud of the work he produced?

HP: I was eight years old the last time I saw Ken, but I grew up with a couple of his Lyrical Abstract pieces prominently displayed in my mother and step-father’s home. It wasn’t until his death in 1997, when I re-connected with his family and saw the entirety of his work, that I began to understand how extraordinarily talented he was. When the collection came to me in Seattle, I was overwhelmed by the intensity, depth, and breadth of the work he created during his short lifetime. I have come to love all of the work, appreciating each different era for its skill and technique. There are a few, though, that are my absolute favorites (Bakaty’s Wall, Sheep Meadow Red Sky, and the Trane’s Sleeve series).

Grand Image: Why did you decide to become a curator? Do you feel like your father’s work influenced that?

HP: I trained in the theatre but became interested in documentary filmmaking in the 1990s. I found a day job in Seattle transferring people’s home movies to video and quickly discovered the world of moving image preservation. I realized I would rather take care of movies than make them. My path eventually took me to the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections where I established the moving image preservation program to care for film and video in the collection and worked as the Moving Image Curator for almost 20 years.

When I received Ken’s collection from my Nebraska relatives, I put my skills to good use archiving all of Ken’s work—assigning unique identification numbers, documenting each piece, and creating a searchable database to be able to share the work with others. I wouldn’t have been able to curate Ken’s work without everything I learned curating film and video collections at the UW. It has been a very helpful and fortuitous marriage of skills, talents, and passion.

Grand Image: Tell me more about your curatorial work. What was the highlight of your career?

HP: My work at the University of Washington involved film and videotape collections that focused on the Pacific Northwest. One of my favorite projects was bringing an orphaned collection of 1920s 35mm nitrate film, newsreels of local events on the Washington Coast, back to the community. A documentary about the collection sums up the project to bring the Newsfilm of Gray’s Harbor County back to life. But bringing local television news, especially the KIRO-TV news library to Special Collections was the apex of my work at the UW. The collection comprises every single story that aired on the Seattle CBS affiliate from 1975 through the mid-2010s and is a complete record of local history, similar to the documentation provided by newspapers over the past century. The reporting may be biased, the choice of stories may have been selective, but the relentless everyday nature of the news documents the history of our region in a way few other collections could. It was used by producers from all over the world, giving the material a reach of multiple millions of audience members in a way that books don’t often have the power to do.

Grand Image: What is your favorite piece of your father’s and why?

HP: Bakaty’s Wall. My stepsister grew up on Long Island and lived in Manhattan for years. At some point during one of my visits, we were walking down Houston Street and a garden caught my attention—it was a green oasis in the midst of urban NY. When I spent time with Ken’s collection, the Bakaty’s Wall series was intriguing. The pieces looked tropical, which seemed extremely out of character for someone who rarely left Manhattan, so I did a little research and turned up some interesting facts.

It turns out that the green space I saw is the Liz Christy Community Garden, the first New York City approved community garden, located at Bowery and Houston Streets. Christy, an artist, organized the Green Guerillas, part of a larger grass-roots movement to address urban decay in New York City and beyond.

Looking at the skyline of the building, I figured out its address and discovered that it was originally built in 1863 for soldiers returning from the Civil War and later became a saloon known as “most degraded destination on the Bowery,” earning the twisted nickname "Suicide Hall." It was closed in the early 1900s during an attempt to clean up the area and became the Liberty Hotel, inexpensive lodging with a somewhat more innocuous reputation than its predecessor. A cooperative of female artists took over the building in the 1960s and it was demolished in 2005 despite efforts to give it historic preservation status.

I was still curious about who or what as a “Bakaty.” It turns out it was Mike Bakaty. He lived and worked in the building at 295 Bowery and operated Fineline Tattoo from his apartment during a prohibition against tattooing in New York City from 1961 to 1997. Bakaty was issued the first license when the tattoo ban was lifted and opened a storefront space rather than continuing to work in his apartment. A highly respected and internationally renowned tattoo artist, Mike passed away in 2014. I’m not entirely sure how Mike and Ken knew each other, but they must have run in the same circles. Both were fine artists working and showing in New York in the 1970s. It was a pretty tight community back then so one could assume that their paths crossed. Bakaty was a sculptor, who worked with fiberglass resin. He has an “artist file” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, but it’s his later work is what garnered attention. Most notably, he was featured in Tattooed New York, a 2017 exhibition at the New-York Historical Society and there are endless articles and podcasts about Mike’s influence and artistry.

Digging into Ken’s work is like untangling a ball of fascinating yarn! The connections are endlessly exciting because Ken seems to be 6 Degrees of Separation from anyone you can think of. I love the Bakaty’s Wall series and the story behind it makes it all the more meaningful.

Grand Image: What do Kenneth’s color and style choices say about him as a person?

HP: Ken grew up in Nebraska and, after driving through the state on a research trip in 2022, I saw the vast open skies dotted with clouds, the shades of blue, the intense yellows, the vibrant greens in the landscape, and realized that those influences found their way into his work. It seems he was always fascinated by color. The Smithsonian oral history is filled with references to color and technique. He touches on theory, explorations of color, the influence his teachers and mentors had on his use of color, and he touches on the work of other artists’ use of color, too. He was serious about his work and constantly challenged himself, learning, reading, going to shows, talking with colleagues and peers. His work was everything to him and he devoted his life to painting.

Grand Image: What artists inspire you? What do you like about them?

HP: Sadly, I didn’t inherit a drop of my parent’s artistic talent, so I’m constantly in awe of the actual mechanics of painting and creating visual art. I recently visited the studios of Ronnie Landfield, William Stone, Nancy Barber, Elaine Grove and Dan Christensen while on a research trip to New York. Seeing how they work, the spaces they inhabit, their discipline, and creative process was absolutely revelatory.

Grand Image: If you could have Kenneth’s artwork hung anywhere in the world, where would you like that to be and why?

HP: Ken and the artists in his cohort deserve far more recognition than received “back in the day.” Some of them were featured in High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967-1975 Curated by Katy Siegel but I feel that there is more to be done to highlight their contribution to art history. Seeing a retrospective of Ken’s work in New York, the city where he lived and worked for most of his life, would be incredibly meaningful. On the other end of the spectrum, I think that his work would be appreciated in his home state of Nebraska, as well. Nebraska has produced a lot of amazing artists, Dan Christensen among them, and the Museum of Nebraska Art recently purchased on of Ken’s lyrical abstracts to bring his work to the attention of those in his home state.

Grand Image: How would you like the world to see and remember Kenneth?

HP: Ken was part of the ever-changing art scene of the 1960s and 1970s and is 6 Degrees of separation from just about anyone you can name from that era. Looking at the list of luminaries who used to hang out at Max’s Kansas City gives you an idea of the circles he traveled in and was connected to. Because he was more interested in painting than promoting his work, Ken has become a footnote in art history. I would love for the world to see and experience the vibrancy and scope of his painting so they can appreciate it as much as I do! I am constantly surprised by how dedicated he was to his work, how much people loved him and enjoyed his company, how prolific and how private he was. I am forever grateful that I’ve been able to connect with the father I never really knew by diving into the work that was his all-consuming passion. I hope other people enjoy his work as much as I do.

Grand Image: Do you have any advice for the children of artists?

HP: It is a daunting and emotional task but can be enormously satisfying. The first thing to do is get a handle on what you have. A simple inventory, a photograph (iPhone pics are perfect), and a unique ID for every piece will get you a long way to understanding the collection. Once you know what you have, you can make decisions on how to move forward and make choices about whether it’s best to sell, show, or donate the work. I’ve enjoyed reaching out to professionals who understand the art market and are willing to guide me on my journey to finding homes for all of Ken’s paintings. I’ve also stopped being shy about promoting his work and am now willing to explore every opportunity I can think of to share it with the world. Also, researching the historical context of Ken’s work has been incredibly satisfying and endlessly fascinating. The biggest piece of advice I have, though, is to be willing to let go. The work is an extension of your parent and holds their energy, their vision of the world, their creativity. Regardless of your relationship with them, letting go can be harder than you think. I have had to say goodbye to a few pieces, knowing full well that there are hundreds more, releasing them so they can live on without me, Ken, or the family. I do love the thought of his work being enjoyed by others. That is one of the drivers to keep working on my inheritance from a man I never really knew.